Pennylands Archaeology and Research

Through the recent plans by the Great Steward of Scotland’s Dumfries House Trust for the erection of new project buildings on the 12-acre site of the former camp, archaeologists were called in to examine and record the physical layout, various uses of the camp and its numerous buildings. A range of intriguing finds from the entire period of the camps use have been unearthed, examined, recorded and stored.

Cumnock History Group came together with Addyman Archaeology and Sue Morrison’s Oral History Research and Training Consultancy, in early 2016 and successfully applied to the Heritage Lottery fund to run a research and oral history project.

In early 2016, archaeologists returned to the site of the camp as the now overgrown field was to be developed for the Dumfries House Farm Education Centre. Over some five months, the remains of the hut bases, walls, concrete paths and roads, fence posts, and substantial drainage systems were revealed as the field was stripped, and their locations carefully recorded to reconstruct the camp for the first time since the last families left in the 1950s.

After the 1950s the camp had been dismantled and most of the valuable materials used for post-War Britain: timber frames, and panels, roofing material, and concrete slabs, but the foundations of the huts remained. These sometimes preserved traces of interior features like partition walls and stove bases, and the toilet and ablution blocks could also be identified.

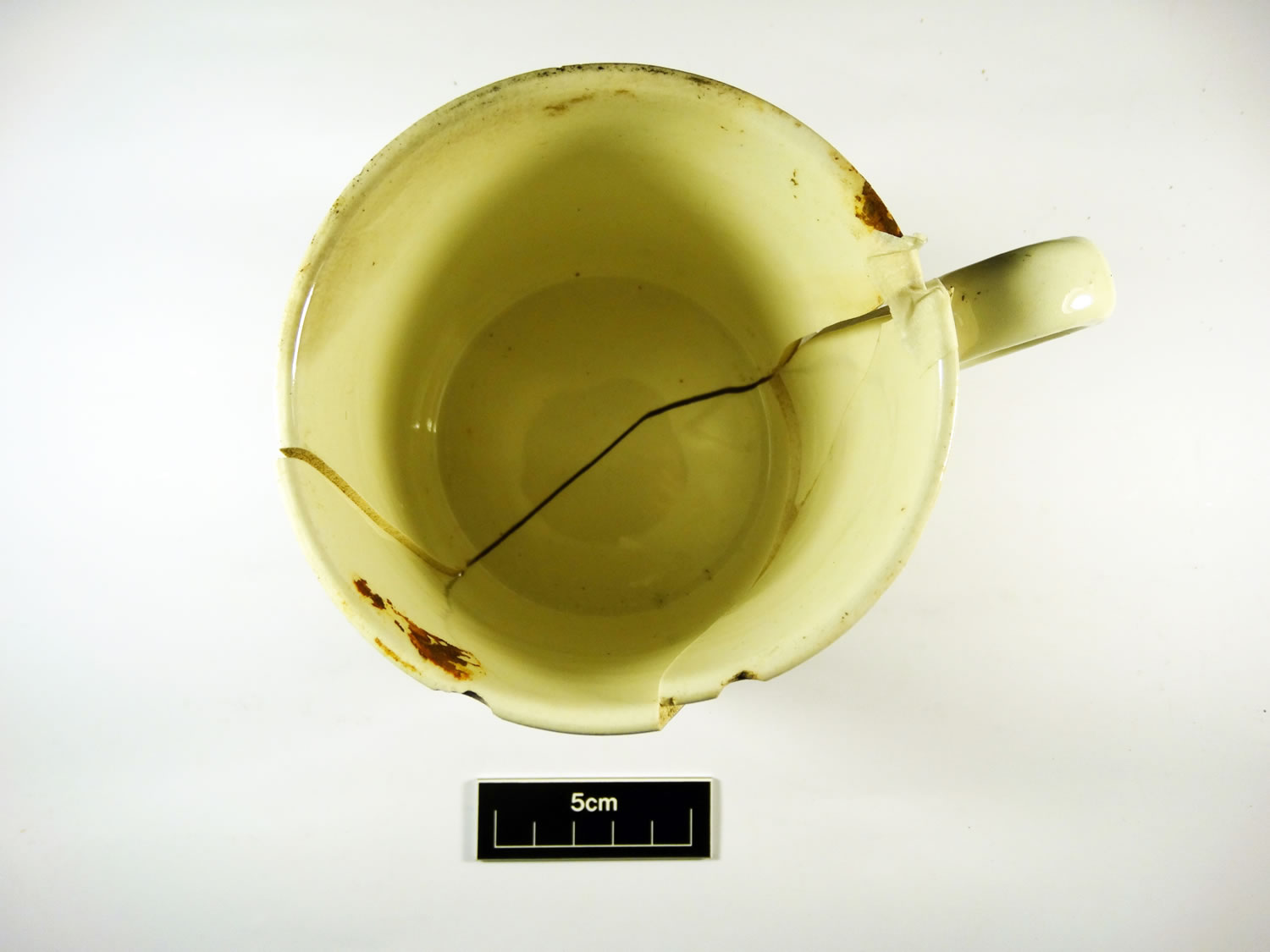

The archaeological work also retrieved a large number of finds from the various uses of the camp – NAAFI ware cups, plates and bowls; bottles and glassware, shoe-polish tins, and even elements of German army uniforms. Life for the civilian families in the camp is seen in the toys – marbles, toy cars, a bicycle – left behind when the camp was abandoned.

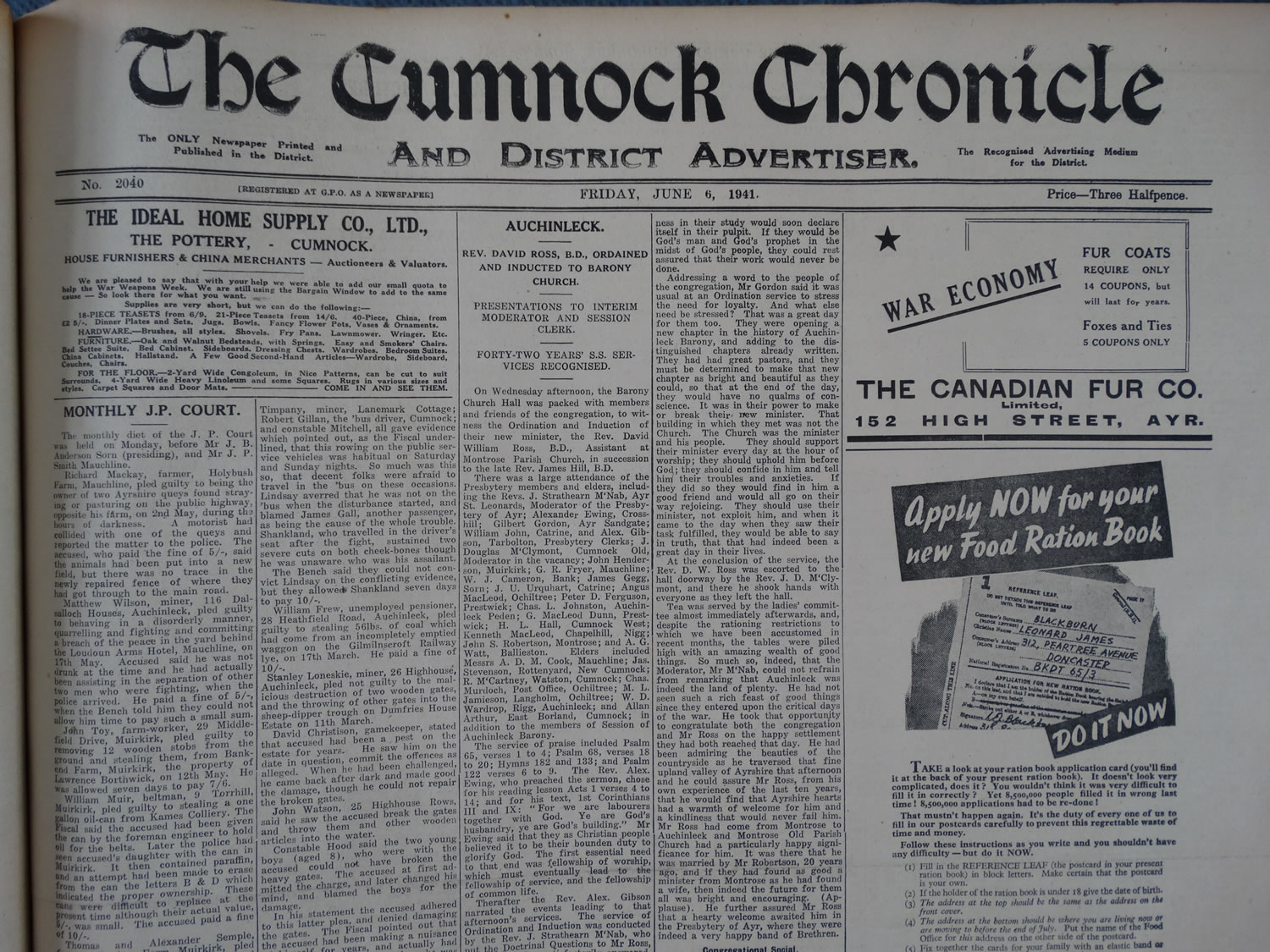

We ran 2 full day sessions in desk research training for 8 volunteers in April 2017 and provided a 5-page Guide to Historic Research complied by Sue Morrison and Bobby Grierson, Pennylands Project manager alongside an extensive resource list. The hands-on training was mainly based at the Baird Institute in Cumnock who hold the local newspaper archive.

We also looked at online resources such as Scotland’s People, Hansard and the National Newspaper archive. We visited the local Ayrshire archives at Auchincruive and examined Valuation Rolls and Ayr County Council minutes, local library collections and the Cumnock and Auchinleck archives at the Burns Monument Centre in Kilmarnock – all bore fruit and we now have an archive of over 1,000 research documents, reports, articles, films, photographs and interviews from each of the camp’s four phases - some made public for the first time on this website.

We organised regular research sessions at the Baird Institute, Cumnock and searched through 20 years of newspaper archives to identify any articles relating to Pennylands. We shared these finds through email conversations and on our Pennylands Facebook page which had the effect of opening this up to a world-wide audience reaching French, Polish and German contacts but also nationally and locally where people were willing to share items and information with us.

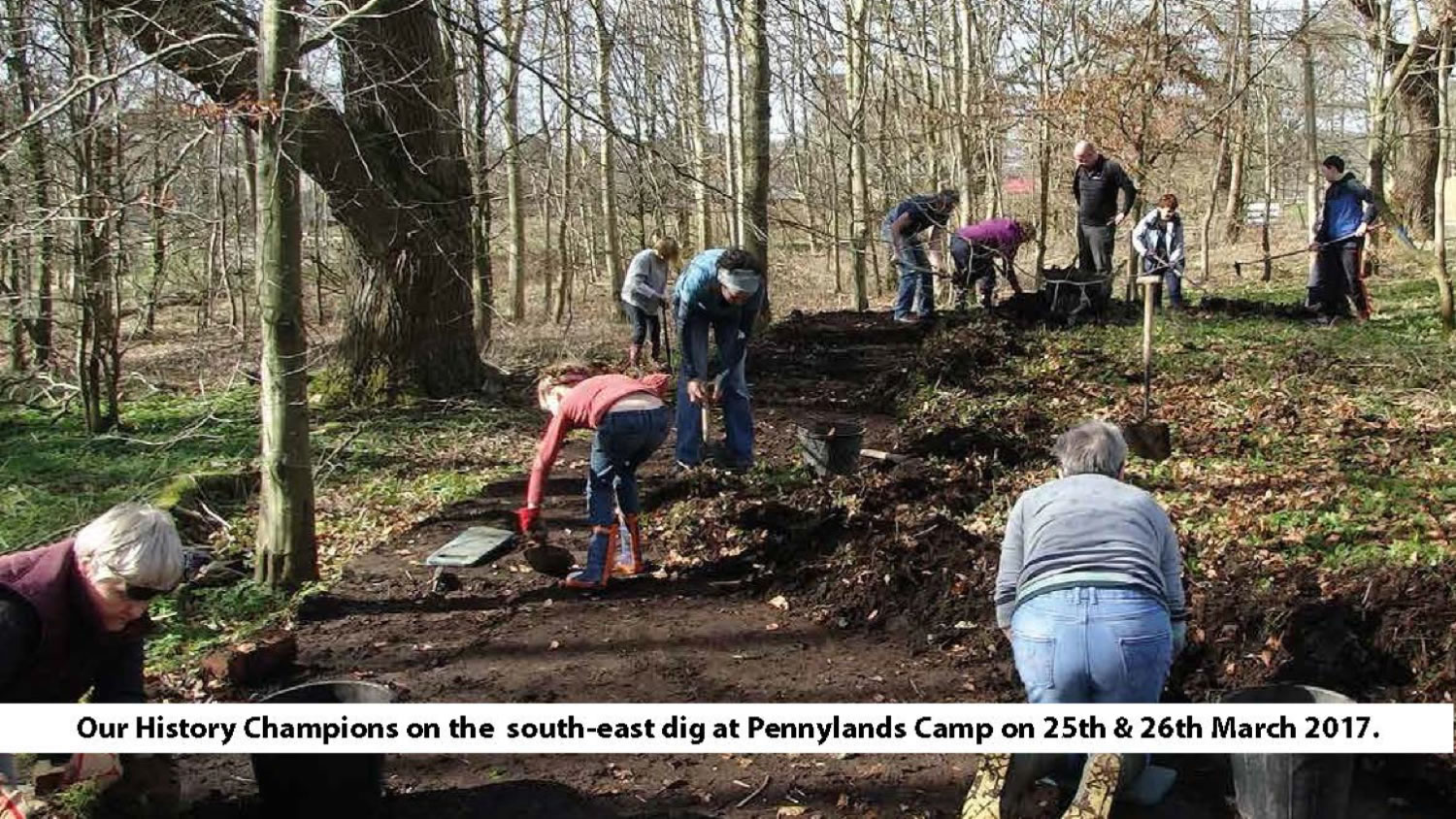

The community excavation was focused on the last surviving section of the camp, located in the south-east corner. Over the two days at the end of March, nine buildings were surveyed and recorded, comprising five accommodation blocks, two possible stores, a shower/washing block and a probable toilet block.

One building was fully uncovered and drawings were made. This was revealed to be a former wash house containing 30 sets of sinks/showers and several drains on the south side. In addition, an accommodation block was partially uncovered. Once the buildings had been recorded, the site was backfilled and reinstated.

Around 30 volunteers participated in the excavation and a similar number stopped as they passed by to share information. Four of them had lived in the camp as children. The volunteers could learn more about the various skills involved in archaeological excavation, ranging from drawing and photography to the excavation of specific areas with a hand-tool.

The community excavation provided an opportunity for the volunteers and those who visited the site to be involved in a practical way in helping to uncover the story of Pennylands Camp during its various phases. This work added to the records from the earlier excavations at the camp and the results now form part of the general record after the camp was finally abandoned in the late 1950s.

The results of the excavation have been added to the oral testimony, archive research and artefacts from the community project to generate an almost complete story of the camp.