Miners Rows

Research by Bobby Grierson

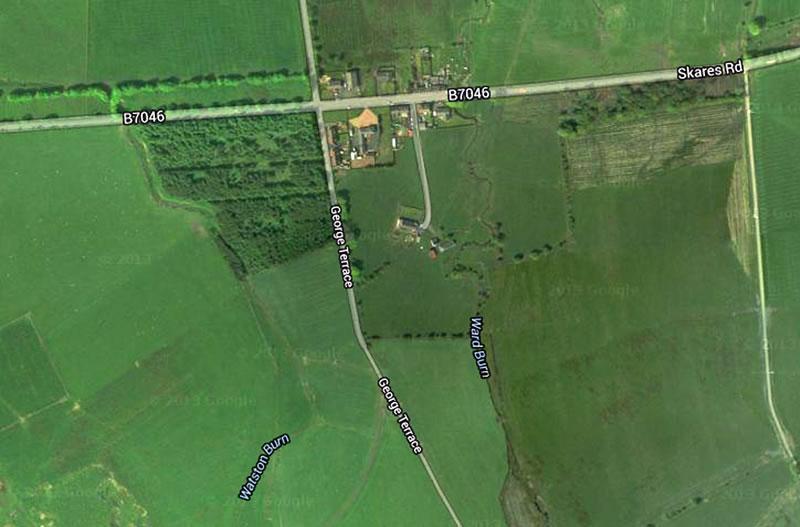

The mining village of Skares, named after the old farm of Skares, lies about four miles south-west of Cumnock and 700 feet above sea level.

On the Ordnance Survey map of 1860 there was a block of about 4 cottages in existence on the north of Skares Road called Crichton Row. Directly to the south of this was Whitesmuir Farm and directly west was Skares Farm.

On the Ordnance Survey map of 1860 there was a block of about 4 cottages in existence on the north of Skares Road called Crichton Row. Directly to the south of this was Whitesmuir Farm and directly west was Skares Farm.

William Baird & Company built a row of stone-built cottages in the early 1870s to house the miners who worked in the pits at Dykes (1865-1894 and to the east), Hindsward (1880-1959 to the south) and Whitehill (1897-1965 to the north). The Old Row was built along the south side of the road just to the north of Skares farm, which ceased to exist. About twenty years later two other rows, the New Raw and the Tap Raw, running behind the first and parallel to it were added. Within 10 years of this some other cottages were erected privately to the east end of the village. The population steadily increased and by the early 50s reached about 540 inhabitants.

Skares railway station served the village, which was originally part of the Ayr and Cumnock Branch on the Glasgow and South Western Railway. The station opened on 1 July 1872, and closed on 10 September 1951 and was situated towards the north of the village. A regular bus service also operated between Skares and Cumnock.

Skares railway station served the village, which was originally part of the Ayr and Cumnock Branch on the Glasgow and South Western Railway. The station opened on 1 July 1872, and closed on 10 September 1951 and was situated towards the north of the village. A regular bus service also operated between Skares and Cumnock.

When Keir Hardie came to Cumnock in 1880 to organise the Ayrshire miners, the working and living conditions of miners could only be described as shocking. The miners’ rows were damp, mostly 2 roomed, outside toilets and washhouses, poor running water and lit by oil lamps. These houses often held families of 8 or more and some took in lodgers. The mine owners owned and were responsible for the upkeep of these rows so complaints about the living conditions were often not made in case people lost their jobs and therefore their houses.

By the early 1930s the only 2 pits operating in Cumnock Parish were Garrallan (closed in 1960) and Whitehill. Scenes of depression and decay accompanied this period and general economic conditions limited demand for coal and rationalization sometimes meant shortage of work.

Whitehill Colliery was a deep mine colliery and was serviced by rail running between Dykes Junction and the colliery. By the mid 30s the mine company had improved the site by removing and reconstructing the ambulance room and constructing the pithead baths. The pit entrance was below the central tower and the baths were on the right and the locker rooms were arranged end to end with the bathhouse behind them. These were built to accommodate 462 men. The exterior of the building was finished in cream-coloured cement rendering. The restyled colliery buildings were opened on 6th July 1934 and cost £8,580.

With the nationalisation of the coal industry after the war Whitehill was taken over by the National Coal Board in January 1947 with the NCB flag being unfurled by James Finn the oldest worker at the time. Whitehall continued operating until flooding in 1965 resulted in closure thereby ending over 200 years of mining in Cumnock Parish.

With the nationalisation of the coal industry after the war Whitehill was taken over by the National Coal Board in January 1947 with the NCB flag being unfurled by James Finn the oldest worker at the time. Whitehall continued operating until flooding in 1965 resulted in closure thereby ending over 200 years of mining in Cumnock Parish.

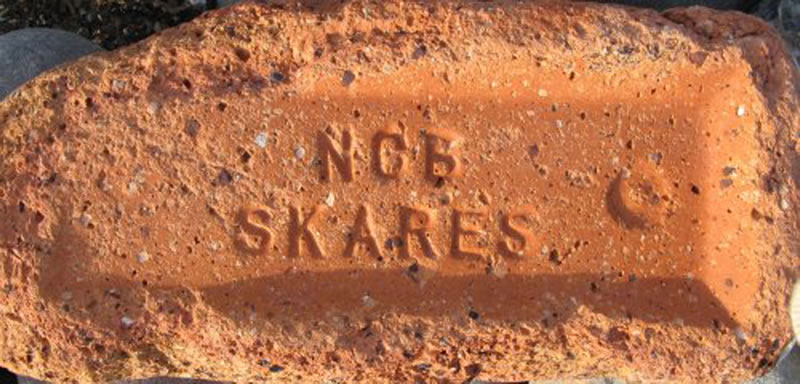

Skares brick works was situated to the north of the mine and was operated by the National Coal Board from 1954-1969 and then by the Scottish Brick Corporation from 1969 to 1984 and thereafter by GISCOL from 1984 – 1987. It had 1 Hoffman Kiln with 28 Chambers and produced 47,000 bricks a day with 16 men. Each brick weighed 10lbs and was fired for 10 days and emerged as 8lb bricks. Coal fired kiln. The blaes (waste deposit of colliery spoils and spent oil shale) to supply the works come from Whitehill and Hindsward Colliery. The Brickworks and Colliery occupied 12.5 hectares of land. In the 1960’s, the manufacture of bricks and excavation of coal ceased and the site was decommissioned. But it is said that Skares produced bricks up until the early 90’s when bricks still left the works as haulage contractors moved approximately 2-3 million stockpiled bricks at discounted rates.

The recycling company, Digit Site Services purchased the land from local farmers in 2000. The site consisted of three main areas: Skares brickworks, the Whitehill Colliery spoil heap or bing and former agricultural land and woodland degraded by flooding from spoil heap water run-off and after extensive environmental intervention mixed woodland and grass was planted over the entire site. The regenerated woodland and wetland is now a rich habitat for a range of plants, animals and birds.

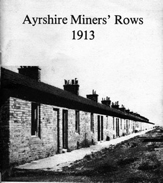

Containing about 110 two-apartment houses and built in three rows, with one of the rows having a kitchen.

From Ayrshire Miners’ Rows 1913 - Evidence submitted to the Royal Commission on Housing (Scotland) by Thomas McKerrell and James Brown for the Ayrshire Miners' Union.

Old Raw or Front Row - The paths are unpaved, the front being fairly clean, but the back is rather dirty, with pools of water here and there. There are forty-two dwellings here, built of stone, and the rent is £5 a year, exclusive of rates. There is a dry-closet for every five houses, and a washing-house for every eight. There are also ash-pits and coal-houses, but the usefulness of these is marred, in our opinion by all of them - the washing-house, coal-house, closet, and ash-pit - being built together practically under one roof. The size of the kitchen is 14 feet by 11 feet, the room 10 feet by 10 feet.

There is a supply of gravitation water, but all the tenants complain about the quality of the water. It is said to be brought from a burn quite near, assisted by a receiving tank, also quite near, which, as might be expected, is discoloured in rainy weather. There is a scullery attached.

New Raw or Middle Row - There are forty houses in the second, or Middle Row. It is built of brick, and the dimensions, rents, and accommodation are the same as the front row, minus the scullery and one tenant less for each closet.

The one marked difference is the concrete pavement in front of the doors. This gives the row a nice, clean appearance, and is really a boon to the womenfolk.

Tap Raw or Back Row - The Back Row consists of thirty-six houses. It is the same in every particular as the second row. Again we saw the difference the concrete pavements made. These should be before every door. The fronts were clean in spite of a rather sluggish open syvor (sewer) and a badly bottomed roadway for vehicles. There are gardens, but only a few cultivated.

By the early 1900s Skares had its fair share of social, educational and sports activities. Skares Memorial Hall opened in 1922 to commemorate the 14 Skares men who gave their lives in WW1. The hall had reading and games rooms with seating for 200 where wedding receptions and concerts were held and where various social groups and public meetings met. These included; the Free Gardeners, Rechabites, Juvenile Football Club, Brass Band, Dramatic Club, Quoiting Club, Phonetic Class, Good Templars and an Ambulance Corps. Various football teams were also formed; Skares Victoria, Skares Athletic, Skares United, Skares Brunton Lads and of course the famous Skares Bluebells.

By the early 1900s Skares had its fair share of social, educational and sports activities. Skares Memorial Hall opened in 1922 to commemorate the 14 Skares men who gave their lives in WW1. The hall had reading and games rooms with seating for 200 where wedding receptions and concerts were held and where various social groups and public meetings met. These included; the Free Gardeners, Rechabites, Juvenile Football Club, Brass Band, Dramatic Club, Quoiting Club, Phonetic Class, Good Templars and an Ambulance Corps. Various football teams were also formed; Skares Victoria, Skares Athletic, Skares United, Skares Brunton Lads and of course the famous Skares Bluebells.

The annual Skares reunion was also popular where ex inhabitants returned to the village to meet up with old friends. Whippet racing was also a popular pastime with many men owning more than one dog.

Primary schoolchildren attended nearby Garrallan School but due to increasing demand a new brick-built school was built in Skares, capable of holding 200 pupils. Children over 12 attended the nearby Cumnock School. Around 1904 the Parish School Board purchased a new piano for the school as the old one had been gnawed by rats! Facilities for further education were offered in the continuation classes to young people aged 15-18 where discussion groups, country and modern dancing and youth service classes were all well attended. Skares primary continued as a one-teacher school until 1966 having only 7 pupils, when it closed.

Primary schoolchildren attended nearby Garrallan School but due to increasing demand a new brick-built school was built in Skares, capable of holding 200 pupils. Children over 12 attended the nearby Cumnock School. Around 1904 the Parish School Board purchased a new piano for the school as the old one had been gnawed by rats! Facilities for further education were offered in the continuation classes to young people aged 15-18 where discussion groups, country and modern dancing and youth service classes were all well attended. Skares primary continued as a one-teacher school until 1966 having only 7 pupils, when it closed.

There was a Mission Hall in the Old Raw at No’s, 47 and 48, which operated from 1911 and held services every Sunday, and regular church buses ran weekly to Cumnock. Cumnock ministers held services for schools once a month during school hours. This Raw had a sub Post Office and Lugar Iron Works Co-operative society store both operating from No’s 45/46.

The majority of Skares men were miners in the nearby pits but a local haulage contractor; potato merchant and local farms employed some men. Women, when employed, found work in surrounding farms, in Cumnock or in the mills at Catrine.

The majority of Skares men were miners in the nearby pits but a local haulage contractor; potato merchant and local farms employed some men. Women, when employed, found work in surrounding farms, in Cumnock or in the mills at Catrine.

In 1949, as part of a wider Cumnock town council housing strategy, new housing schemes were built in Craigens and Netherthird to rehouse some of the inhabitants of Skares, the Old stone-built Row being demolished in the late 50s and the New and Tap rows in the early 60s. Many Skares folk had already moved into new council houses in Cumnock including Wylie Crescent, Glenlamont and Michie Street. Some cottages still survive at Skares but the demolition of the ‘raws’ saw the end on an almost 100 year era for the close-knit community of Skares.

George Johnstone - The Tap Raw houses were entered through the door from the street and had a sink under the window looking onto the street. There was a bed recess (mine) in the front room, a fireplace and a small kitchenette. The back room was mum and dads bedroom and had a window looking onto the middle raw. The outside toilets were simply that, a row of individual cubicles behind the washhouse. Don't remember if there were wash hand basins but I don't think so. If I remember correctly they were allocated to an individual house. Don't remember too much detail of the washhouses.

Jane Kelly Rutherford - The Rutherford’s had 2 houses knocked into one. My mum said the grate had to be cleaned out, black leaded and brassoed every morning. She accidentally spilt the brasso in the fire and nearly set the house on fire! Everybody had their day in the washhouse, you had to heat the water first and then you were there the whole day.

Albert Raeburn - The washhouses had a cauldron with a fire below it and there was a mangle near the window. I used to keep my bike in the washhouse, which was never locked - nobody stole from each other in the raws. My granny lived in 116 and brought up 8 children in their 1 bedroom house. One of her sons lived in the top row and had 12 children, also brought up in a room and kitchen. The Rutherford’s house was the 1st and 2nd house in the middle row knocked into one. Old Ned and Graham stayed there.

Rita Mitchell (nee Morris) - To me there is nowhere like Skares was, and anyone who came from there will say the same. Everybody knew everybody else and they were always ready to help anyone that needed it. You could go out and leave your door open without worrying about anything being pinched. In the summer we used to all go on a picnic doon the Blackwater when it was nice, and we'd go for walks roon the Pluck.

My mother sometimes took us up to the Covenanters monument up the Knockdunder hills. She used to take us picking raspberries to make jam in the summer, and when the brambles were ready she'd take us to pick them and scribes to make jelly. It was guid. We used to take our mother's clothes pole and loup the burn. At Halloween we'd go roon knocking on doors and we'd sing or say a poem and get sweeties, nuts and fruit. We were always made welcome. At Hogmanay some folk would go first fittin'.

My granny (Meg Stevenson) used to have big steak pies in to feed us and anybody else that came in. I remember my granta coming hame frae the pub with auld Bally Shirkie. Bally used to take me through to the fire in the bedroom and teach me auld Irish songs. I don't think he could go hame till he sobered up a bit. It was a great wee place. We had no gas or electricity and the women all had their own day for using the washhoose. When we had a bath it was usually in a zinc bath in front of the fire with water het up in the washhoose boiler. It was hard work for the women folk having no electricity and having to cook on a coal fire, but they managed weel.

We had the co-operative shop with Danny Hall managing it. Ned Rutherford had the fish and chip shop. Jean usually worked in it. There was the mission hall where we went to Sunday School, and the Memorial hall where most folk held their wedding receptions, and sometimes we had concerts there. We even had oor ain fitba team the 'Skares Bluebell'. We had oor ain piper as weel. Jim Stewart used to go up the auld bing near Martin Pringles farm (Hindsward) and walk back and forward playing the bagpipes. He was good, but when you're a wean you don't appreciate it. It's an awfa noise tae ye. I appreciate the pipes now though. When I hear them in Sheffield, the hair on the back of my neck really does stand up.

It certainly was a great wee place and I could go on and on aboot it, but it would take too long. I've lived in Sheffield now for nearly 46 years, and it's no a bad place to stay, but there'll never be anywhere like Skares and the Skares folk to me.

May Williams - Skares between the wars

I was born Mary Phillips 2nd daughter of Sam and Mary Phillips, née Shirkie, on 7th March 1922, 82 Skares Row, in the village of Skares near Cumnock in Ayrshire, Scotland.

My father was a coal miner in Whitehill Pit, where he worked for 50 years. My mother was a hard working lady. She bore 10 children and worked on the farms all her working life. As my dad did not have big wages, mother did people’s washing and worked in the fields every summer. They were a great pair and very, very happy. Her sister was the farmer's wife at Rottenrow Farm, between Skares and Ochiltree.

We were very poor but very happy. Our meals all came from the land. Dad had a vegetable garden and homing pigeons. He caught rabbits and hares and mother made the loveliest soups and stews. We ate lots of trout from the streams and the fishmonger came round every week with herrings and whiteys, so we had fish twice a week as well. We got milk and eggs from the farms.

I had four sisters and five brothers. And we all attended the village school, Skares School, and then at 11 years old we went on to Garrallan School and had to walk a mile and a half to this school. Hail, rain or snow we had to hoof it to the school. Sometimes we were snowed in and could not get there for a week or more in the wild winter.

We were all very healthy, but poorly dressed. We only got new clothes once a year. Our grandmother knitted and sewed to help clothe us. I wore all my sister’s hand me downs, even her boots which pinched my toes, hence my bunions today.

Father was our shoe repairer and solderer. He was a first aid man at the pit, also doctor at home. He was very strict with us, but a very good father. He taught us to dance and sing. Mother taught us to cook, wash and sew and even taught us to paperhang and paint.

We had lots of friends, pals we called them, as mostly everyone in the village had from 5 to 20 children. Most children went to Sunday school and the Band of Hope. We had a Gala Day once a year, when the farmer loaned the horse and cart to take us out to one of his fields, where we had sandwiches and cookies, with milk or tea. Then lots of fun with singing and dancing and games. Even the fathers and mothers had races and tug of war. It was real fun. If you won a race you got sixpence and everyone got a penny. I think the Mums and Dads paid into a kitty every week.

Our little village always had a football team, the Skares Bluebells. Most boys played football and men played quoits. There were always men relaxing in the wood playing cards. In winter it was curling on the loch. My dad didn’t play he was always walking. Himself and a few other dads used to have a string of children away walking for miles, especially on Sundays after church, while the mothers prepared dinner. We went hiking for miles and there was a cycling club if you could afford a bike. There were not many cars about and buses ran every 20 minutes into our local towns, to Ayr and Cumnock. In Cumnock at the Auld Kirk there were buses to Kilmarnock, Glasgow, Ayr and Dumfries and all the local villages around about. Most of the time people walked as there wasn’t always enough money for fares.

When the “Talkies” started at the picture house, as it was called then, we got once a year, that was on New Year’s Day. It was a wonderful day for us kids.

As time went on and we grew up a bit things got slightly better, but what a struggle dad and mother must have had making ends meet. Mind you the soup pot was always on the hob and boy what soup it was.

Skares was a little mining village. Most families only had two rooms and a scullery. Up until I was about 7 years old we had no water in the house. Our water came from pumps distributed between about 90 houses. Every 20 houses shared a pump; hence we had to carry the water in pails from the pump to our houses and the wash-houses, where everyone did their laundry. Then the washing was dried out in the green or in the wood, everyone sharing the wash houses and the clothes lines.

When I was about 5 or 6 years old I took diphtheria as there was a big epidemic and quite a few people died. Most of the germs came from the dry lavatories which were all shared between two houses. Sometimes there were some not so hygienic neighbours, who didn’t always manage to find the proper outlet for their urine and mother always had to scrub the toilet seats before us children were allowed to use them. Poor mother.

However, by the time I was 8 years old we got new drainage put in to the houses and running water laid on. Also, water lavatories put in but we still had to share. By this time, we were all growing up and my sister and I were at work. We worked on the farms at first, having left school at thirteen. I worked at Auchlin and then Creoch. We also slept on the farms so things were a bit easier for mother at home. My eldest sister worked at farms for 4 years and I done 7 years. Then the war was on and I moved away from my hometown to Annan to work for the war effort away from the farms and into a hostel, working in a canteen for munitions workers. So from the age of thirteen until I was 24 I only went home for holidays.

It was great in the hostel. We lived in and everyone worked and played hard. I was able to send some money home to help out with the younger brothers and sisters. My sister joined the ATS as an ambulance driver. She married a Canadian and went to live in Canada after the war ended.

After the war, about 1949, my parents and family moved into a new house, with all mod cons, in Craigens Road, Netherthird.

With thanks to May’s daughter Mary Restarick.

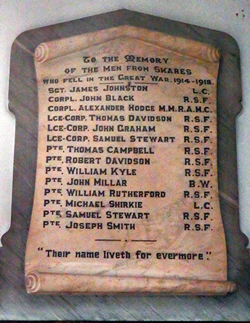

Many local men enlisted from the rows to fight in the Great War. Fourteen of them gave their lives. They are commemorated on 2 memorials, the original which is now in the Cumnock Old Parish Church in the Square and on a new one, which was erected in Skares in November 2103. These men are also on the War Memorial at Cumnock new cemetery on Glaisnock Road Cumnock.

Many local men enlisted from the rows to fight in the Great War. Fourteen of them gave their lives. They are commemorated on 2 memorials, the original which is now in the Cumnock Old Parish Church in the Square and on a new one, which was erected in Skares in November 2103. These men are also on the War Memorial at Cumnock new cemetery on Glaisnock Road Cumnock.

To the Memory Of The Men Of Skares

Who Fell In The Great War 1914-1918

Sgt James Johnston LC

Corp John Black RSF

Corp Alexander Hodge MM RAMC

Lanc Corp Thomas Davidson RSF

Lanc Corp John Graham RSF

Lanc Corp Samuel Stewart RSF

Pte Thomas Campbell RSF

Pte Robert Davidson RSF

Pte William Kyle RSF

Pte John Millar BW

Pte William Rutherford RSF

Pte Michael Shirkie LC

Pte Samuel Stewart RSF

Pte Joseph Smith RSF

However some Skares men survived the war and details of them and the above can be found on the Cumnock History group research blog on Cumnock men and women who served in WW1 here:

http://cumnocksoldiers.blogspot.co.uk/search?q=skares

We are always interested in further information about the Skares Rows. If you have any photos, stories etc please email: info@cumnockhistorygroup.org

Skares Galleries

Download the pdf of the Shirkie Family in Skares HERE

Download the pdf of the 1911 Census and 1915 Valuation Rolls for all Skares residents HERE

Sources

Strawhorn J, The New History of Cumnock, 1966, Town Council of Cumnock.

Strawhorn J, Boyd W, Ayrshire – The Third Statistical Account of Scotland, 1951, Oliver & Boyd, London & Edinburgh.

McKerrell T, Brown J, Ayrshire Miners' Rows 1913, 1979, Ayrshire Archaelogical and Natural History Society.

The Scotsman, 1891-1918, Edinburgh.

The Edinburgh Gazette, 1920.

The Sunday Post, 23rd Aug 1925.

The Aberdeen Journal, 25 August 1896.

Edinburgh Evening News, 23 June 1893.

Dover Express, 31st Dec 1948.

The Herald, Thursday 20 April 2006.

Remediation of Skares Brickworks & Whitehill Colliery, Digit Site Services, 1999-2000

Cumnock Chronicle, August 27 2014.

From Ayrshire Miners’ Rows 1913 - Evidence submitted to the Royal Commission on Housing (Scotland) by Thomas McKerrell and James Brown for the Ayrshire Miners' Union.

These rows are situated about 3 miles from Cumnock on the Cumnock and Muirkirk Road.

Row No. 1

This row is built of brick, and the walls are cemented. The roofs are slated. There are 18 houses in this row, and the population is 101. The houses have a kitchen 15 feet by 14 feet and two small rooms 9 feet by 6 feet each. There are no fires in the room, and the tenants complain they are very damp. The windows are very small, measuring 4 feet 10 inches in height and 2 feet 4 inches wide. The windows are made so that they cannot be opened. There are neither wash-houses nor coalhouses, and the coals are kept under the beds. For this population of 101 there are three closets with doors on them and three ashpits in front of the houses. A syvor runs down the front of the houses, and there was a considerable amount of filth at the grating at the end of the syvor. The refuse taken out of the syvor is dumped down on the ground immediately outside the door of the end house.

Row No. 2

This is a replica of Row No. 1. The population was 113. The open cesspool was in a filthy condition. There are 18 houses with three closets and ashpits built in front of the doors. One of the tenants said to us at this row “You should have come here in the Summer time; it costs us about 1s a week for flypapers.”

Row No. 3

This row is in exactly the same position as row No. 2, but there are only 16 houses in this row with a population of 73.

Row No. 4

This row is built of brick, with walls cemented, but the roof is nearly flat and is not slated, but covered with tarcloth. There are 24 houses of 2 apartments. The kitchen is 16 feet by 9 feet, and the room 9 feet by 8 feet. There are no fires in the rooms, and the windows are permanently fastened. The rent is 5s 6d per month. There are three closets and three ashpits for these 24 houses. About half the houses were empty, and the population of those inhabited numbered 56.

Row No. 5

This row is exactly the same as Row No. 4. The roofs are tarred instead of slated. There are 28 houses with five closets and five ashpits. The rent is the same as row No. 4. A large number of these houses are empty. The population was 80.

Row No. 6

This row is similar to Row No. 5. The houses are constructed in the same manner. There are 30 houses in this row, but on the 13th November, 1913, 21 were empty and only 9 inhabited. There were five closets for this row.

Row No. 7

This is a superior row built of stone, and inhabited by the schoolmaster, policeman, and foremen of various kinds. There are 13 houses, 11 are 2 apartment houses. The kitchen measures 12 feet by 12 feet and the room 10 ½ feet by 10 ½ feet. The other 2 houses are one of 4 apartments and one of 3 apartments. Even in this row no washing houses are provided unless the people build them themselves, and this has been done in several cases. In this row only, are the people provided with coalhouses. The rent of the 2 apartment houses is £4 4s per annum.

Summary

The population of this village will be approximately 600, and there is not a single washing-house for the whole population. With the exception of Row No. 7, there is not even a coal house. The windows are all permanently fastened. The pathways in front of the houses are all unpaved, and in the winter time are in condition of a quagmire. The village is supplied with gravitation water, and there are two wells in every row. The company employs a scavenger. The houses are said to be about 60 years old, and are owned by William Baird & Co., and inhabited by the mining workers of that firm.

From Ayrshire Miners’ Rows 1913 - Evidence submitted to the Royal Commission on Housing (Scotland) by Thomas McKerrell and James Brown for the Ayrshire Miners' Union.

Garallan Rows contain 22 houses, 4 being 2 apartments and 18 single. It is leased from Boswell of Garallan by the Carraden Coal Co. The rent for double house is 2s 1d and 1s 11d for single. The single houses are back to back, and one of these has been halved, one half each being given to tenants, thus making a small room. The double houses measure - the kitchen 14 feet by 12 feet, the room 12 feet by 12 feet. The single houses measure 15 feet by 13 feet. All of these are in a shameful state of repair. We saw in one house a pail placed in bed to catch the water which was coming in from the roof on 4th December, 1913. All of them very damp. We saw another house the roof discoloured and the paper hanging in shreds from the walls. One woman said to us—“Ane has nae heart to clean them, for your work is never seen.” That is not difficult to believe. The floors are of brick tiles and badly broken. The rooms are wooden floored. The paths are unpaved and unspeakably dirty, and there are dirty cesspools in front of the doors. There are six dry-closets, ill-kept and dirty. We saw some of them with at least 3 inches of water lying in them, and some of the seats were covered in filth deposited by children we presume, for no self respecting adult could use them. There are no washing-houses and no coalhouses, the coals are kept below the bed. The water supply, so we were informed, was from field drains. This row is a mile from the town of Old Cumnock.

From Ayrshire Miners’ Rows 1913 - Evidence submitted to the Royal Commission on Housing (Scotland) by Thomas McKerrell and James Brown for the Ayrshire Miners' Union.

These rows are situated on the main road between Cumnock and Muirkirk, 4 miles from Cumnock. There are 4 rows, 2 are built of stone and 2 of brick, and all are slated.

Row No. 1

The first row (nearest Muirkirk) consists of eight houses, but six of them are unoccupied, and one tenant has rented 2 houses and pays 6s 6d per month. There are 8 inmates. There are no closets, no washhouses, and no coalhouses. The only water supply is from a pipe running into a horse trough on the side of the road about 300 yards from the houses.

Row No. 2

The houses in No.2 row are built of stone, and are all single apartment houses, but in some cases a family has rented 2 houses. The house measures 15 feet by 12 feet. There are neither coalhouses nor washhouses. There are 2 closets without doors and ashpits without roofs. There are 10 houses, but 3 of them were empty at the date of this inspection (13th November. 1913). The population was 26. The only water supply is at a pump about 200 or 300 yards away. The rent is 2s a week. Pathways in front of houses are unpaved and very muddy.

Row No. 3

This row is built of brick. There are 10 single apartment houses. There are no washhouses or coalhouses. The people keep their coals below their beds. The apartment measures 17 feet by 14 feet. The rent is 2s 2d a week. There are 2 closets and ashpits. The closets have no doors and the ashpits have no roofs. The population was 33.

Row No. 4

This is also built of brick, and in the same position with regards to conveniences as Row No. 3. There are no washhouses, no coalhouses, and there is one closet without doors for the 12 houses in this row, and one ashpit without a roof. There were 2 empty houses, and the population of this row was 30. The water supply is from the pump which supplies the other rows. The whole adult population of these 4 rows are without any closet accommodation, as owing to the want of privacy (no doors) they cannot use the accommodation provided. The surroundings of the closets are littered with human excrement. The houses are owned by William Baird & Co., and are inhabited by the workers of the pits belonging to that firm in the neighbourhood.

Research by Kay McMeekin

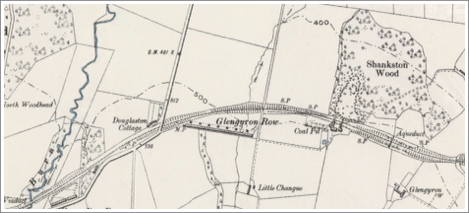

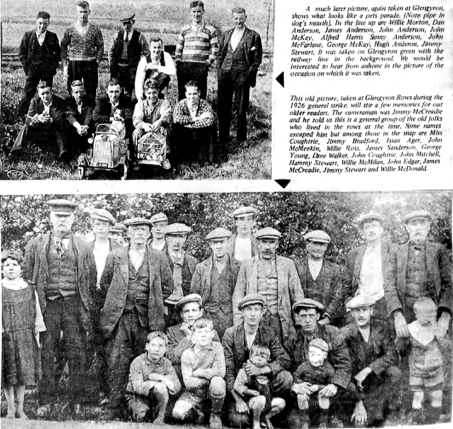

Situated on a hill to the south-west of Cumnock, Glengyron was named after the nearby farm of Glengyron and was built by the Eglinton Iron Company c1872 to house its workforce of coal and iron miners and their families.

The author has been interested in Glengyron Row since taking up family history research. She knew her husband’s family lived there for many years, but unexpectedly found her great grandparents lived there too. By all accounts it was a close-knit community and fondly remembered by those who lived there. Facilities were primitive by our standards; they didn’t get mains water until 1880. Large families lived in mostly two rooms, often with lodgers for extra income.

The author has been interested in Glengyron Row since taking up family history research. She knew her husband’s family lived there for many years, but unexpectedly found her great grandparents lived there too. By all accounts it was a close-knit community and fondly remembered by those who lived there. Facilities were primitive by our standards; they didn’t get mains water until 1880. Large families lived in mostly two rooms, often with lodgers for extra income.

It consisted of a single row of 44 north-facing, houses with one room and one kitchen with box beds. The inadequate outside dry-closets and washing-house were shared by the tenants.

In front of the houses was a green and beyond that the Ayr and Cumnock branch line of the G&SW Railway ran past at the banking. There might have been a halt near the bridge. The nearby stations were at Skares, Dumfries House and Cumnock New Station. The row was occupied from May 1872 - maybe slightly earlier, but after the census of April 1871. Many of the new tenants were miners recruited from England - the Midlands, Cornwall, Durham, and elsewhere. Presumably, they travelled by rail to move to the area.

In front of the houses was a green and beyond that the Ayr and Cumnock branch line of the G&SW Railway ran past at the banking. There might have been a halt near the bridge. The nearby stations were at Skares, Dumfries House and Cumnock New Station. The row was occupied from May 1872 - maybe slightly earlier, but after the census of April 1871. Many of the new tenants were miners recruited from England - the Midlands, Cornwall, Durham, and elsewhere. Presumably, they travelled by rail to move to the area.

The earliest reference to the Row that has been found was the marriage of Elijah Penrose to Louisa Carne on 17 May 1872. Both lived at Glengyron Row. They were originally from Cornwall, fathers both copper miners. They were married by Rev James Murray, Minister of the Old Parish Church. Witness were Eliza Rundell; Marion McGee; James Robertson.

The earliest reference to the Row that has been found was the marriage of Elijah Penrose to Louisa Carne on 17 May 1872. Both lived at Glengyron Row. They were originally from Cornwall, fathers both copper miners. They were married by Rev James Murray, Minister of the Old Parish Church. Witness were Eliza Rundell; Marion McGee; James Robertson.

In the 1875 valuation roll, the owner of the row was Eglinton Iron Company of Lugar. Among the 28 tenants we find the Prices and Yates (Yetts) were from the Dudley area; the Jacksons and McGavocks were from Ireland.

By the 1911 census two of the houses at No 8, inhabited by Andrew Baird and No 37, by Hugh Blackwood, were split differently giving them 3 rooms. The neighbouring houses still had 2 rooms and it isn’t clear how this was achieved (see the 1913 Ayrshire Miners’ Rows Report). Number one was the store at the west-end of the row; latterly No 5 was the reading room.

It was a small, close-knit community and many families lived there for years, their children marrying neighbours’ children. Widows continued to live on in their miners’ cottages.

It was a small, close-knit community and many families lived there for years, their children marrying neighbours’ children. Widows continued to live on in their miners’ cottages.

David Jackson, born in Ireland, appears in the 1875 valuation and lived there until his death in 1909:

- his daughter Harriet married neighbour Joseph Price

- son Samuel married neighbour Elizabeth Yates who was a kinsman of the Prices

- daughter Elizabeth married neighbour John Penrose

- daughter Mary Ann married neighbour Andrew Baird

- son James Jackson married Mary Hyslop from nearby Garallan - maybe he had a bike! In all, he had 11 known children.

Sadly, his son Joseph aged 4 had a horrible accident in 1876 when he fell in front of a wagon at Glengyron Lye, as reported in the Edinburgh Evening News. He died half an hour later.

As well as from Ireland and places in Scotland, families moved in from Cornwall and the Black Country in the English Midlands:

- The Yates, Prices, Rolinsons, Hunts and Jones were all related and came from the Black Country.

- The Penroses, Burleys, Mitchells and Smetherhems were originally copper and tin miners from Cornwall. Some of them stopped off in Durham or Cumberland on their way north.

In the twentieth century, miners from further afield joined the community. In the 1911 census, a Lithuanian family, Gustitas (or Gostar), was at No 11, and a German family under the name of Thomson at No 31.Victor Carballo from Spain was present in 1925 and 1930.

In the twentieth century, miners from further afield joined the community. In the 1911 census, a Lithuanian family, Gustitas (or Gostar), was at No 11, and a German family under the name of Thomson at No 31.Victor Carballo from Spain was present in 1925 and 1930.

The two-year-old Willie Gustitas died after falling into an open fire in 1909 while his mother Catherine went to the store. She was found guilty under the Children Act of failing to take reasonable precaution for the safety of her child, and was fined 20 shillings (£1) or 7 days’ imprisonment.

Around 1939–40, people were moving out of Glengyron Row to live in the new houses in the town. In the 1940 valuation roll, many of the Glengyron Row houses were empty or uninhabitable. The annual rent was £6 and 8 shillings - £6.40p.

From Ayrshire Miners’ Rows 1913 - Evidence submitted to the Royal Commission on Housing (Scotland) by Thomas McKerrell and James Brown for the Ayrshire Miners' Union.

Glengyron Rows are about a mile from Old Cumnock, and are owned by William Baird and Co., Ltd. There are 44 two apartment houses. One of these 2 families have 3 apartments at the expense of other 2 families, who have now only single apartments. The kitchen measures 15 feet by 12 feet, the rooms 10 feet by 9 feet. The rent is £4 16s a year, exclusive of rates. The paths are unpaved, but not very dirty when we saw them on 4th December. 1913. There is one dry-closet for every 3 tenants, coalhouses for each tenant, and a washing house for every 6 tenants. These are all under one roof which, in our opinion, is a bad arrangement. Some of the closets we saw were ill-kept, one with a door off and very filthy. The houses are in a bad state or repair. In one house we saw rain getting in and being caught in a basin. Another we saw with half the window of the room boarded up. We were informed that it had been in this state for a year, in spite of repeated enquires of the tenants as to when it would be glazed. The floors are of brick tiles, and broken. There is a supply of gravitation water taken from the supply of the burgh of Old Cumnock.

Glengyron Rows are about a mile from Old Cumnock, and are owned by William Baird and Co., Ltd. There are 44 two apartment houses. One of these 2 families have 3 apartments at the expense of other 2 families, who have now only single apartments. The kitchen measures 15 feet by 12 feet, the rooms 10 feet by 9 feet. The rent is £4 16s a year, exclusive of rates. The paths are unpaved, but not very dirty when we saw them on 4th December. 1913. There is one dry-closet for every 3 tenants, coalhouses for each tenant, and a washing house for every 6 tenants. These are all under one roof which, in our opinion, is a bad arrangement. Some of the closets we saw were ill-kept, one with a door off and very filthy. The houses are in a bad state or repair. In one house we saw rain getting in and being caught in a basin. Another we saw with half the window of the room boarded up. We were informed that it had been in this state for a year, in spite of repeated enquires of the tenants as to when it would be glazed. The floors are of brick tiles, and broken. There is a supply of gravitation water taken from the supply of the burgh of Old Cumnock.

We are always interested in further information about the Glengyron Rows. If you have any photos, stories etc please email: info@cumnockhistorygroup.org

Sources

Scotland’s People, National Library of Scotland, John Strawhorn; The New History of Cumnock, 1966, Scottish Mining site, Memories of family members, Cumnock Chronicle, The Scotsman, Cumnock Connections family tree, Cumnock History Group.